LAST PAGE

LAST PAGE  RETURN TO INDEX

RETURN TO INDEX

GRAPH 1

This shows all the adjacent manors as wasted, with the exception of BE1 the manor of Bullington on the immediate opposite shore of the Combe Haven valley. A more detailed geography of this valley and the evidence that it was at the time of the invasion a large inland bay is provided in a later chapter. At this stage I seek the indulgence of the reader in accepting that according to my hypothesis Wilting is the correct manor to use as the centre of observation.

Two things are immediately apparent from this visual display. Firstly almost all the manors in the Pevensey Rape at the time of the invasion have much higher values than those in the Hastings Rape. Secondly the values appear to slowly increase the further away from Wilting the manor is situated.

The graph shows values in relation to distance regardless of direction from the site. In consequence blips occur in the middle area of the graph at Ewehurst (ST4). These are caused by the values to the north being different from those to the east and west, at a similar distance. It is therefore necessary when looking at the invasion story to analyse the values of the manors from Wilting along the road to Pevensey to see what this produces on GRAPH 2.

If current historical hypothesis is correct you would expect to see values immediately adjacent to Pevensey reduced dramatically if Jumieges, Poitiers and the Bayeux Tapestry are interpreted as meaning that the Normans landed at Pevensey. However to be fair to the Bayeux Tapestry it does not say they landed at Pevensey and I shall examine this in the next chapter.

GRAPH 2

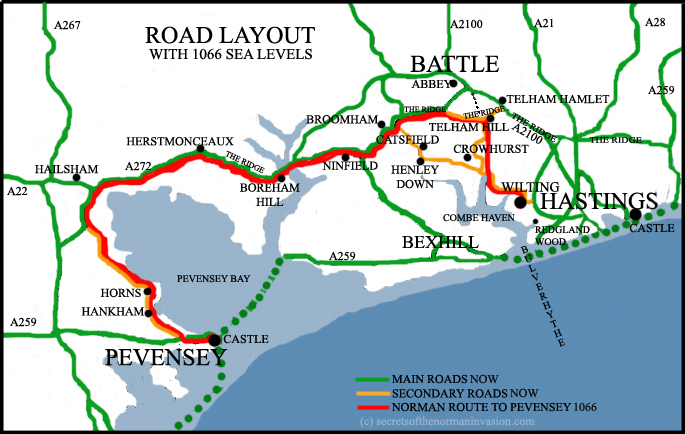

The route that I have used would involve following what was then and now known as the London road out of Wilting. It was nothing more than a track at the time, going to Battle through Crowhurst. Evidence of this still exists going over Sandrock Hill in Crowhurst, through Blacksmiths Field and then along the eastern side of the Combe Haven inlet direct to where Crowhurst Church now stands. This route still exists as a footpath but has been superseded by the development of the fordable route over Hye House hill. The road then passed where Crowhurst church now stands heading up what is now Station Road, but was then the only track in existence, to the top of Telham Hill, where it went straight on to Battle (now also a footpath).

MAP4

This, I would suggest, is the London Road along which William marched his army and was the line of hamlet development before the introduction of the turnpike along the ridge, in the relatively recent 19th century, which provided a faster and safer route to Hastings. If the ridge route proposed by past historians had in any way been developed, as a usable alternative, Crowhurst would not have been used as the main route for coaches prior to this and there would be at least a few properties with a history prior the introduction of the turnpike. As further justification the population centres at Crowhurst, Wilting and Hollington manors would not have developed, as they did, along the linear connections of this main road.

At Telham Hill the road turned left to Broomham. Telham Hill should not be mistaken for Telham on the ridge. Telham hamlet is at the very top of the ridge and not the same place as Telham Hill, lower down to the west and marked on all Ordnance Survey maps. Colloquial and local spoken history concerning the Battle of Hastings refers to Telham Hill and many historians have made the mistake of assuming this means Telham on the ridge. Whilst Telham, as a name, does not feature in any of the manuscripts I have looked at, there is a strong argument that the inclusion of the name in spoken tradition indicates its importance in the events of that day. This matter and others I shall address in the second volume of this document, to be published shortly.

Further confusion is caused by those who do not know the area by the name of the Broomham manor because what was Broomham in 1066 is now where the main road passes through Catsfield. In consequence whilst Catsfield is listed as a separate manor in Domesday this is off the main road to Pevensey on the Crowhurst - Henley Down - Catsfield Road starting in Crowhurst on the far side of the inlet from where the invading army was positioned. Support for this route for the army, via Telham, comes from the fact that Catsfield manor, which lies away from the thoroughfare retained a relatively high value when the manor on the main road, Broomham, was wasted. The road from Telham to Broomham skirted the effective southern boundary of what was to become the land of Battle Abbey, called the Leuga. In consequence it was at that time well established. If the Normans had gone to Pevensey by land using the northern route, further north to Battle, Broomham would have been missed completely taking the direct route from Beechdown Wood to Boreham Hill. retaining higher values, in line with Ninfield and Herstmonceux. On the assumption that the Normans did go to Pevensey during the period of the Invasion, Domesday supports the Wilting - Telham - Broomham - Ninfield route as being the only completely logical one which does not produce contradictions in the relative values.

Living in Crowhurst, at the centre of the area under discussion, I understand this to be the only possible route, given the geography as it was then. Catsfield manor missed being wasted because it was neither on the main route to Pevensey, nor on what was then the main through route along the coast from Hastings. The Combe Haven valley provided a severe obstacle to the immediate West of Hastings and whilst it has been argued (62) that Battle was the only place to exit from what was an effective peninsula, I disagree with this, as anyone will know from a simple study of the five meter water line(63) in the area. The Normans did not need to go further north than Telham if they wanted to go to Pevensey using the major available routes.

MAP 6

Examining Williamson's map it can be seen that Telham Hill is marked where the hamlet of Telham is situated, on the ridge to the northeast, rather than at the actual Telham Hill site directly north of Crowhurst. The Bulverhythe is completely the wrong shape and all the contours of the coast line appear to have taken on an artistic licence far beyond the reliable and verging upon a distortion of known facts. The correct outline, or at least one that is a far more reliable one, is shown on MAP 5

In my opinion Domesday supports the view that the invading army went through Ninfield on the way to Pevensey and as such must have either forded the inlet at the bottom of Boreham Hill, or used a bridge that already existed in some form or other. Any alternative route would have involved far greater logistical problems, because Waller's Haven, the name of the then tidal inlet to the west of Ninfield, below Boreham Hill, divides north and west into a number of tributaries. This inlet requires crossing whether you are travelling to or from Pevensey and Hastings. If this is the case the peninsula argument falls away, since access to the mainland can be reached by ford or path along a 7 kilometre front from this point to beyond Battle directly north-west of Hastings, using recognisable routes that subsequently developed into highways.

The main coast road from Pevensey to Hastings turned left at the junction at the top of Telham Hill to Broomham, without the need to go to Battle (which of course did not exist at that time), continuing to Ninfield and Herstmonceux on the edge of the Pevensey marsh. Without the existence of the town of Battle no purpose was served by taking the northern detour, when a simpler and perfectly satisfactory shorter route existed along the ridge parallel to the sea at Telham. From Herstmonceux it went through, or close to, Hailsham before turning round the bay to the small holdings of Horns and Hankham, where it reached Pevensey. This is an area that is remarkably flat, devoid of any potential camp sites situated at the bottom of a hill of any size.

It is clear from the values shown in Domesday that Pevensey suffered relatively little from the invasion. In fact the Domesday entry for Pevensey indicates that the value before the invasion was 76 shillings and 9 pence. There is no mention at all of loss in value, with the exception that when the Count of Mortain was given the manor by William, when there were only 27 burgesses instead of the previous 28. In consequence I am being gracious in accepting any loss in value. The entry adds that the value at the time of the survey, 20 years later, was then over three times as much, at 323 shilling and 9 pence. Clearly the people of Pevensey had done very well from the invasion in the time that had elapsed. This is hardly consistent with the concept of the ravages of an invading army, as experienced in the Hastings area.

Not being a person versed in the wisdom of historical studies, outside this very narrow interest, I cannot understand how it can be argued that Pevensey could be either the landing site or William's camp site. An invading army has to establish a bridgehead and then consolidate the position. At the time in history that we are looking at there were no modern communications or back up systems. As soon as the men were on foreign soil they needed provisions. The larger the force the more provisions were needed.

According to Domesday there is no evidence that the town of Pevensey was in any way involved in providing William's army with provisions that subsequently reduced the values of the manorial holdings. All the evidence points to the landing and camp being at Wilting or possibly Crowhurst on the Combe Haven valley at the old Port of Hastings, where the reduction in value was greatest. At that site all the manors in a large swathe of countryside running to the East and West of the old London road, which ran North from there, are laid waste. In effect all value was removed by the invading foragers in the time that they were there.

In conclusion the authoritative documentation of the Domesday Survey completely vindicates Wace's claim that Pevensey was little more than a raiding party on the day following the invasion. The evidence of manorial values confirms that this pillage was not by boat, upon the formation of a landing bridgehead. Neither was it upon landing and then moving to Hastings via the invasion fleet, in vessels that the army were unlikely to be accustomed to. The evidence of the Domesday Survey clearly shows the progressive lessening of the impact of the foraging army along the route from Hastings to Pevensey via what was then known as the coastal route. Pevensey itself seems to have escaped almost unscathed. It is known that the resident army of men, held under duty from manors to the King - the Fryd - had been stood down after spending the Summer manning the forts of the south coast. The geographical position of Pevensey made it a particularly unlikely landing site, since the castle almost totally covered the very small peninsula upon which it stood. To land anywhere in the immediate vicinity of that castle, upon the most probable basis that there would be an armed defence, would be a tactical disaster that no commander of William's ability would have made. Even if he had prior knowledge of the standing down of the guard I do not believe it credible, in an age where communication was so slow, that he would risk everything by allowing Harold to reoccupy a stronghold immediately adjacent to the proposed landing site, in the time it would take to receive the reconnaissance report. Whilst William would undoubtedly have had spies at the main ports the Channel formed a formidable obstacle to the passage of information. All the reports show it to be impassable for the fleet for some time prior to the invasion due to the weather. Given these circumstances a prudent commander would seek to land upon an unfortified shore.

Those manors in the vicinity of Pevensey suffered moderate losses according to their original value and position in relation to the distance from the camp at Hastings and position in relation to the main coastal route. There is no other possible explanation to the figures involved. Whilst loss of value was measurable in the Pevensey area it was nothing like the devastation suffered in the area to the north of the Combe Haven valley where there is hardly a manor left intact. The proposal that the invading army landed somewhere unknown near Pevensey, on the main bay area, does not stand up to scrutiny. All the manors around the bay show the same characteristics where loss is equated to distance from Hastings. If the proposal that Pevensey were the landing site was to be supported in any way there would be a sustainable deviation from the norm. This does not happen and I propose that the evidence of the Domesday Survey, taken with the absence of any archaeological evidence, of any kind, that this story has no foundation.

A study of the manors in the area immediately surrounding the Combe Haven valley in 1066 is shown on GRAPH 3

GRAPH 3

GRAPH 3 clearly shows that even 20 years after the Battle that Wilting and Crowhurst, the manors immediately to the North of the Combe Haven valley, are still the least well recovered of all manors in Sussex. The reason being that they suffered the highest degree of ravaging by the invading army, taking the longest to recover. This is the logical and only explanation for the dip in the chart.

The Domesday Survey proves conclusively that Pevensey and the manors in the immediate vicinity could definitely not have been William's camp or landing site. It shows that the manors within the Hastings Rape were those that suffered the devastation. It shows Wilting and Crowhurst as the centre of this activity and supports unequivocally the concept of the landing and invasion site being in one of those manors, both of which have extensive shore lines on what is known locally by the people of Crowhurst and Wilting as the Bulverhythe. This area was a large inland natural harbour with accompanying bay of shallow, relatively still, water. In consequence I shall now refer in this document to this bay as the Bulverhythe in the same sense as those who still live in the area, unlike many academics who site Bulverhythe at the entrance to the Combe Haven valley, which retains the name. It is my view that Bulverhythe, as a name still in use today, is an important element of the tradition of spoken history surviving boundary and name changes, the significance of which I shall address later.

The Domesday Book

NEXT CHAPTER

RETURN TO INDEX

RETURN TO INDEX